In 1977 it was hard to get a job. Only a year before, students like me who had finished school with a Leaving Certificate could find work in the major banks, the post office or Telecom. But times had changed, and unemployment was on the rise. On Saturday morning, I bought the Age, circled jobs, and waited until Monday morning to make my phone calls at a phone booth. The jobs were often gone by the time I got through. One day, I saw a job as a court clerk. I had done Legal Studies at school, and it was a subject I really enjoyed. I loved learning about different legal cases and the precedents they established or built upon. My enthusiasm must have landed me the interview.

As I had no work clothes, I borrowed a blue wrap around skirt with matching shoes from Cat with whom I shared a flat. The shoes had a wedge heel which was a novelty for me. I had exactly 40 cents left for the week which was the cost of the tram ride from the top of Milton Street to Flinders Street station. The solicitor’s office was located in a turn of the century building on Flinders Street near Elizabeth Street.

I walked up two flights of marble stairs, holding onto the heavy wooden balustrade so I wouldn’t go over on my ankles. On the landing was a heavy wooden door. I stepped into a small office and his secretary ushered me into the solicitor’s room. A kindly old gent sat behind a desk piled high with folders, tied with pink legal tape. He invited me to sit down and tell him why I wanted the job.

‘Legal studies was my favourite subject at school. I love reading about cases and the stories they tell. You know, like Donoghue v Stevenson. That snail in the bottle, and she actually won! Duty of care and all that.’

He smiled. ‘Tell me about yourself, about your family and what you want to do with your life.’

‘My father died a couple of months ago and I’m looking for work now. I’m a real hard worker, you won’t regret giving me the job.’

‘Can you see yourself finishing your studies?’

‘Oh, yes! I’d love to finish my HSC and maybe go to uni. I’d love to study Law.’

‘Well, in this job you will be getting files ready and taking them to court. There’s a lot of running around but you will meet interesting people. It’s a good start for someone interested in the Law.’

‘Does this mean I have the job?’ I asked hopefully.

‘Well, I do have another couple of girls to interview but you are definitely on my shortlist. You don’t have a phone number, do you?’

I shook my head.

Well, give me a call tomorrow morning at nine and I’ll let you know.’

I shook his hand firmly with good eye contact. I had this in the bag.

Outside, the sun promised a beautiful day ahead. As I had spent my last 40c on the tram ride, I began my long walk home. The tram ride had been a pleasant half hour trip but the walk in Cat’s shoes proved much more arduous. It seemed to take forever just to get to Domain Road and there were still a few kilometres to go. I walked past all the modern office blocks and hotels on St Kilda Road, feet aching, and mouth parched. I walked past wolf-whistling construction workers, eyes firmly fixed on the footpath, self-conscious about how I looked. I walked past confident men in suits and tall women in tight skirts trying to keep up with the pace.

I walked past the boarded-up factory where my father once worked, and eventually reached St Kilda town hall where a few years earlier I had requested permission to keep a bus filled with animals in front of St Kilda marina! There were memories everywhere I looked, yet I still had quite a few more blocks to walk. All I wanted to do was to take the shoes off and drink a glass of cold water.

Finally, I reached Milton Street and the block of flats where I lived with three friends. When I arrived home, the girls were out. I put Cat’s shoes back into her room, wiggled my blistered toes and sat down, tucking my feet under my bottom in one of our large 1930’s armchairs. I sipped on a cup of instant coffee with two and a half sugars and closed my eyes. I never borrowed Cat’s shoes again.

The next day, I took some money from the kitty to make the phone call. I was excited for my first real job in a lawyer’s office. The phone rang three times before my future boss answered.

’Thanks for ringing back. It was a tough decision. I can see that you would make an excellent court clerk and I’d love to have you on board. But when I got home last night, my neighbour came by. His daughter is looking for a position and, well, I’ve known the family for over 30 years. I felt I had to give her a chance. I’m sure you understand the position I’m in.’

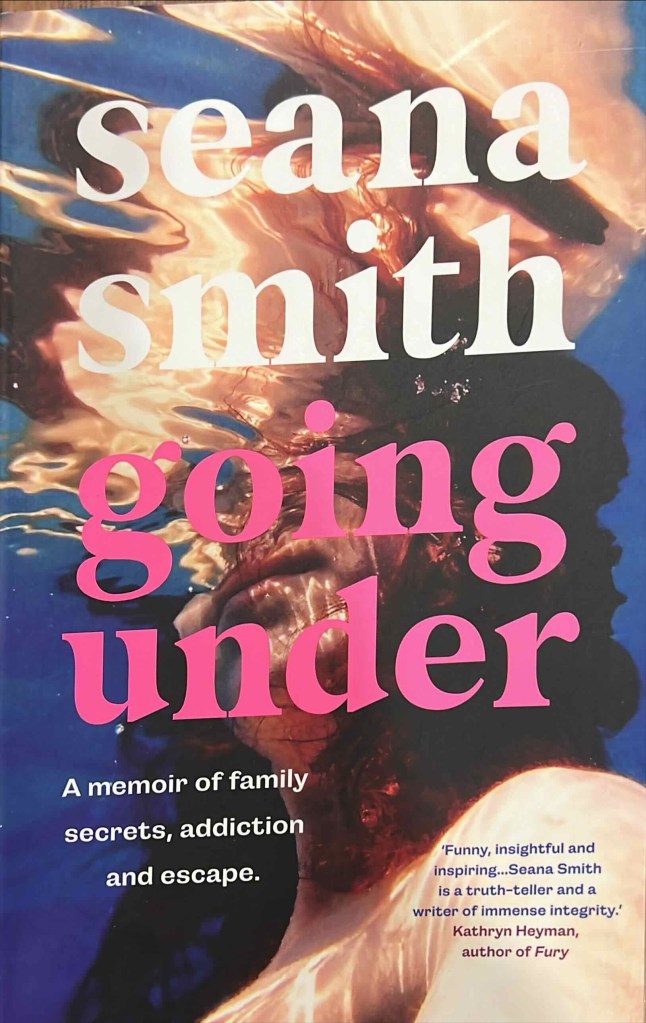

I choked on my words, said thank you and hung up. It was a moment when my life could have taken a different turn and I was fully aware of the chance I had lost. I never did pursue a legal career. In one of those odd turns of fate, it was to be my daughter (above right) who would finish her Law degree and be admitted to the Bar.