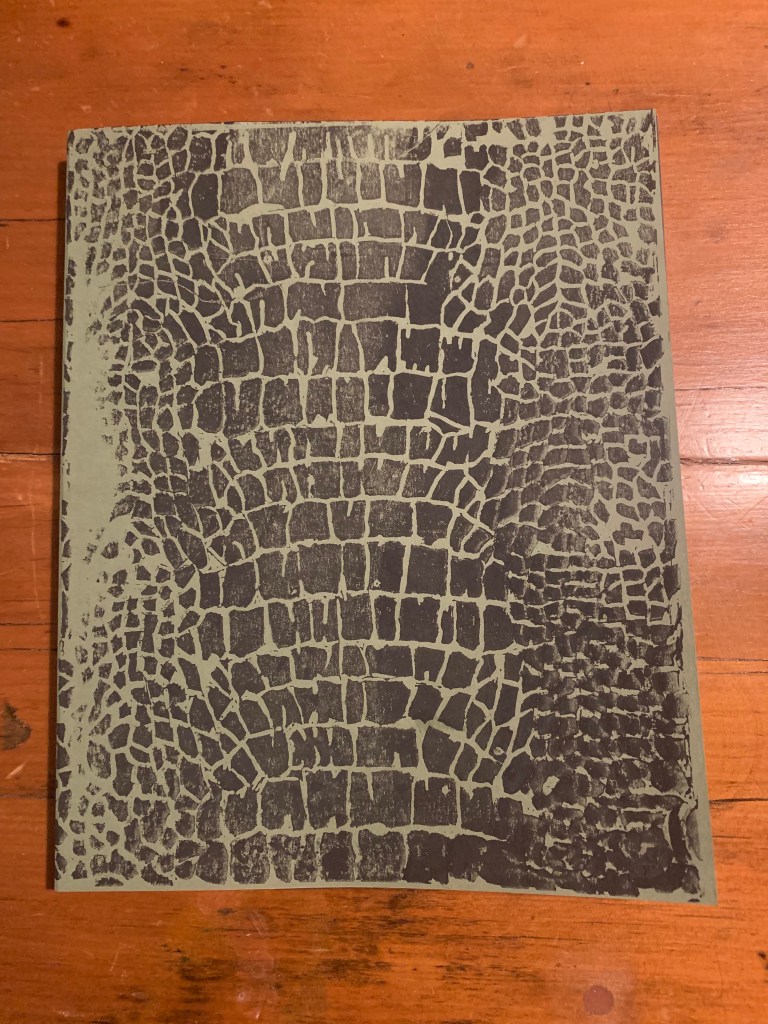

I caress a first edition, limited print run of a book of photographs. The cover, green and black, is the pattern of a crocodile’s skin. Nothing else suggests what the book is about. I am intrigued.

An A5 insert explains the genesis of the book. The author, Rory King, a talented young photographer, has long been fascinated with Val Plumwood, a trailblazing Eco-feminist who lived on Plumwood Mountain in a hand-hewn bush retreat. Her ground-breaking work on anthropocentrism has influenced the way ecology is viewed – humans as part of the web of life and not at the very centre of it.

King’s photographs of Plumwood’s cottage and the rainforest in which it stands, are intimate, matte black and white images that play with light and shade. Some are fleeting moments, fragmentary, a blink of the eye. Others capture the lush growth of the forest floor. King also includes photographs of the East Alligator lagoon situated in Kakadu National Park, where he followed Plumwood’s footsteps to the exact location where she was savagely attacked by a saltwater crocodile. I find these photographs the most evocative in the book, in part because of my own memories of a trip to East Arnhem Land and in part because crocodiles take me back to my childhood, when I listened to Seppi, the crocodile hunter, tell stories of pursuing crocodiles along the Nile.

Not only is the book evocative and visually luminous, it also has a tactile allure. The recycled paper has an ecological appeal, befitting Plumwood’s philosophy. I have an urge not only to view but to touch and feel the images on the page. There are so many details to explore – the stacked books in front of Plumwood’s fireplace, baskets and trinkets, a banjo on a divan. Then there are shimmering individual leaves, reflections in water, a build-up of silt along a riverbed. My fingers trace the branches of a tree, the back of a crocodile floating in the water…

Plumwood is published by Tall Poppy Press and is available at www.tallpoppypress.xyz