My sister gave me a gift the last time I saw her. She handed me a little red felt box and said, ‘I know this isn’t your kind of thing, but I want you to have it. And don’t sell it.’ When I opened the box, it contained a small brooch, possibly made of ivory. I recoiled. She knows full well what I think about the ivory trade. What to do?

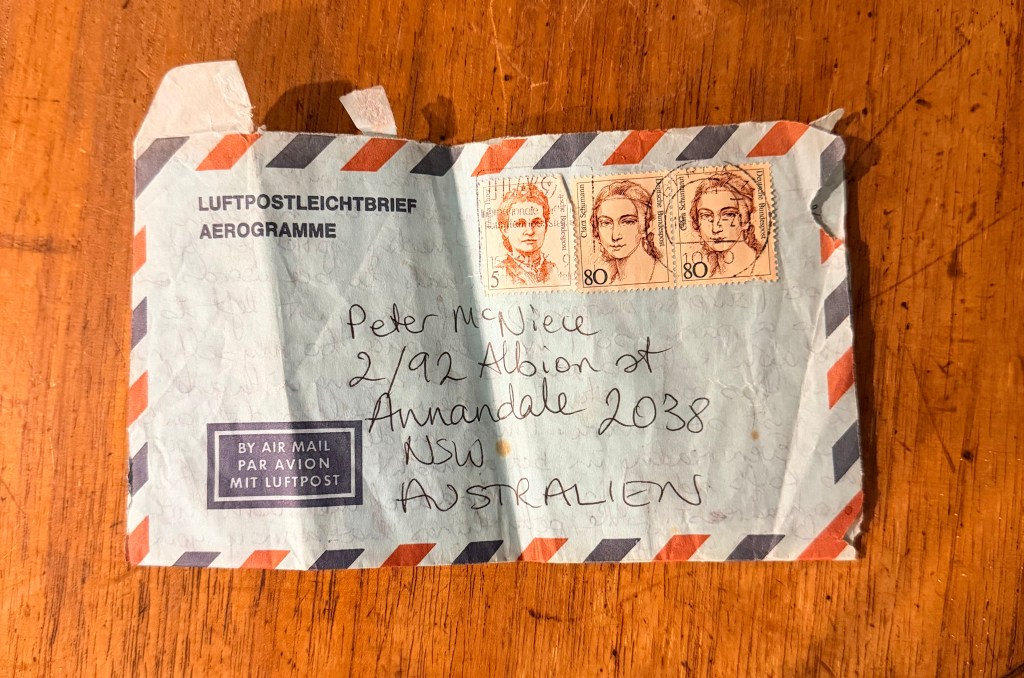

There is a ten-year difference between my sister and me but it has often felt more like twenty or thirty. From a young age, she had to mother me and although we lived apart for many years of my childhood, she still sees herself in that role. I cannot see that ever changing. This has made situations like receiving unwanted gifts difficult between us. I did say that while it was beautifully carved, I would not wear it, but she still pressed it into my hands. So now I have it, along with a large gold pendant with a silver coin from my birth year, and a couple of German porcelain figurines, apparently collectors’ items, stored away in a cupboard.

I keep reading about baby boomers wanting to downsize and give their precious belongings to the next generation, to no avail. Nobody wants the things we have loved and cherished and it breaks my heart to think of my beautiful mahogany chest going to an op shop one day. Of course, I am aware that I will have no say in the matter. My daughter will have enough of a headache going through my books and personal belongings. Why should I burden her with ivory and kitsch figurines as well?

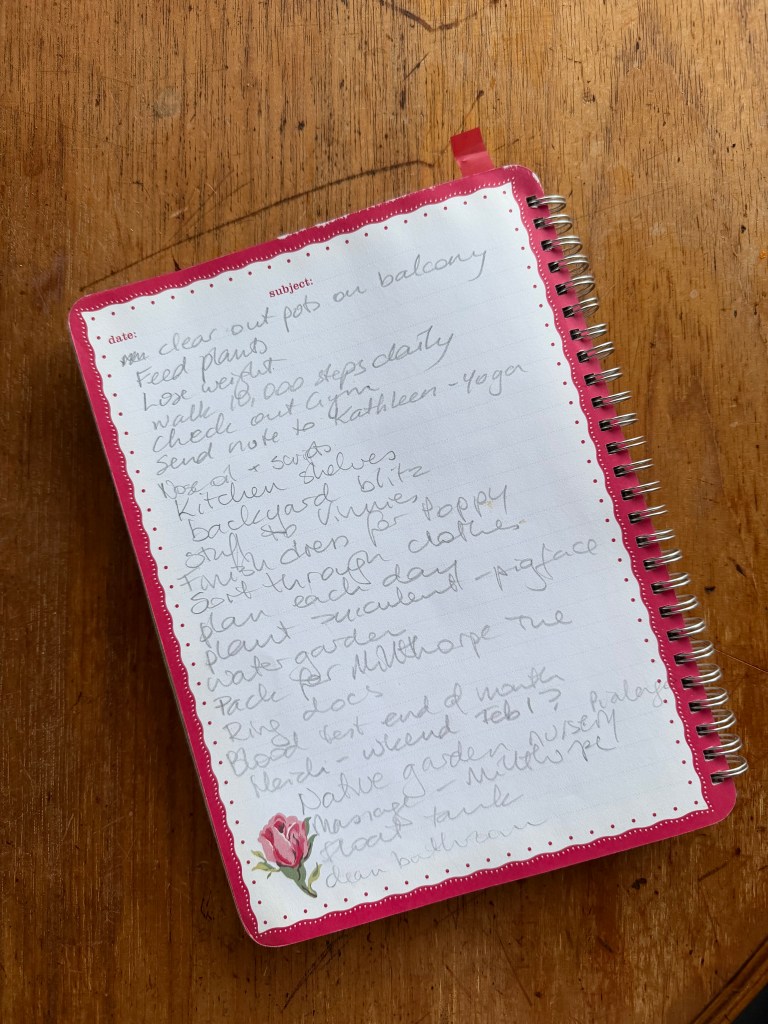

I am loyal to a fault and will probably keep things I do not like because I do not want to offend the giver. Or maybe I keep them because I really do not know what to do with them and cannot make the decision to try to sell the items or give them away. To whom? Many of my friends are of a similar age and certainly do not want anything else to add to their stash. They too are at the ‘Do you want this?’ stage of their lives.

When I think of our house when I was growing up, there were probably no more than a few hundred items in the whole house. I would have more items in my kitchen now than we had in that entire house. My wardrobe consisted of two pairs of jeans, maybe three blouses, a couple of windcheaters, two jumpers, a jacket and a parka. Footwear was a pair of sandshoes, a pair of leather shoes, sandals and a pair of treads. I wore them day in and day out as we had no uniforms at school. Now we would call that a capsule wardrobe.

Reminiscing about times gone by does not help with my present-day quandary. Do I keep the brooch, do I sell it, or take it to the op shop? I am not a Marie Kondo who can say arigato, think nice thoughts and then send it on its way. I have much more in common with the hamster I kept when I was eight. Keep stuffing it in even when it seems no more can possibly fit, then run furiously on the wheel, hoping that if I run long enough, I will arrive at a decision.