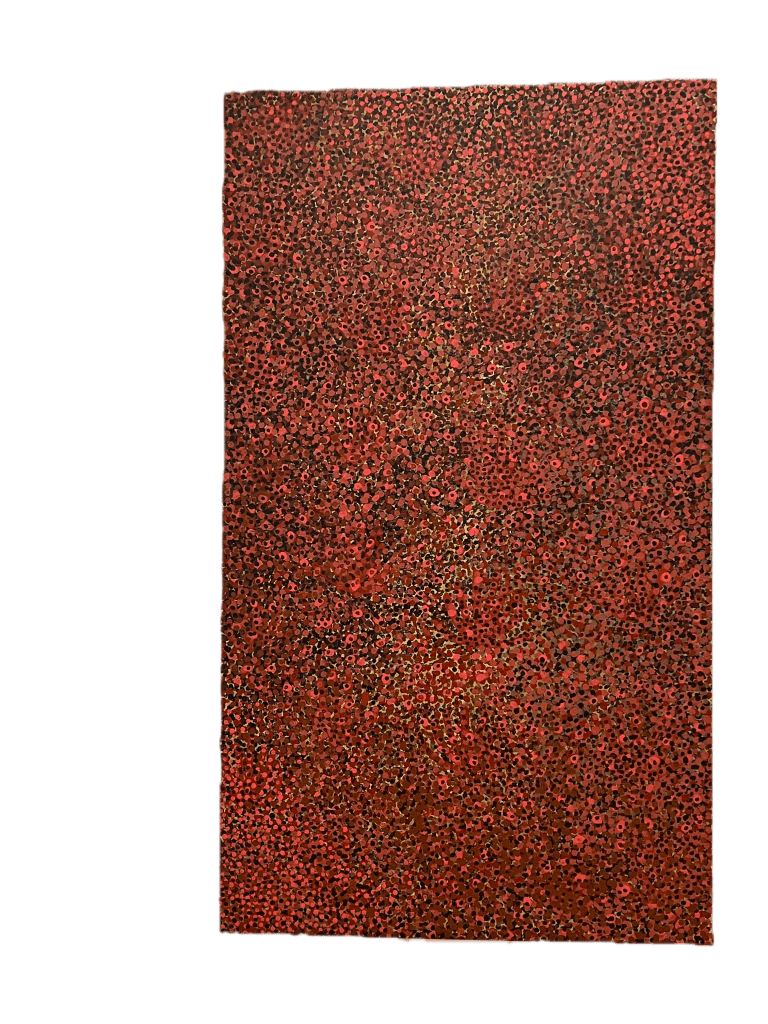

Untitled, 1990, Emily Kam Kngwarray

A visit to view Emily Kam Kngwarray’s works at the National Gallery provoked much thought about how Western eyes view Aboriginal art. I freely admit that I have no training or understanding of how to view art, nor do I understand the desert culture from where the artwork originated.

Kngwarray was an eminent contemporary 20th century painter, whose work has paved the way for many other Indigenous women to engage in making art. Her career only spanned eight years but, in that time, she created a huge number of significant paintings and batiks which depict Dreamtime stories of which she was a custodian, and she also painted her Country around Utopia. Many of her paintings depict yam and emu dreaming, seasons and the contours of her land.

The sheer magnitude of her paintings amazed me. Her most famous one, titled ‘Earth’s Creation’, is 2.7m high and 6.3m wide. It takes up the length of a wall in the gallery. This painting is mesmerising and awe-inspiring. It fetched over $1,000 000 at an art auction in 2007. From my readings about her, what makes her unique and celebrated is not just the sheer size of her canvases but the range of different styles she employed as well as her layering technique using a cornucopia of colours, which is quite different to other Aboriginal art. Some art critics consider her to be on par with Monet, which begs the question why she has to be compared to a French male artist to establish her importance.

I couldn’t help wondering about this old woman who took up painting in later years. Besides the joy of painting and having her work exhibited in many countries, how did the work and fame benefit her and her community? How did she feel about having her work taken out of Utopia, stretched, mounted, and displayed in galleries where only the privileged can view them?

The artists would have produced these paintings with the canvas lying on the ground. Kngwarray may have kneeled on and maybe even walked upon her paintings. To reach the spaces in the center of the canvas, she would have touched them all over. Now, they are hung in a gallery with security guards ensuring that nobody comes anywhere near her works. How did she feel about this? Alienated? Are we viewing Aboriginal art, which most of us don’t really understand, how white people once viewed First Nations people as ‘noble savages’, curios there for our entertainment? I have no answers to my questions, only a sense of discomfiture as I view these pieces out of context.

I understand Kgnwarray’s importance as the first female painter to be recognised in an art movement that was dominated by men and the path she created for other women to follow in her footsteps. I can also see the significant benefit of recognising the value of First Nations artists and the great potential it offers to make a livelihood. And yet.

Perhaps one appeal of an exhibition like this one is the multitude of questions it raises for each of us to consider, regardless of the conclusions we may reach.